On Thursday, OpenAI announced that they had trained a language model. They used a large training dataset and showed that the resulting model was useful for downstream tasks where training data is scarce. They announced the new model with a puffy press release, complete with this animation (below) featuring dancing text. They demonstrated that their model could produce realistic-looking text and warned that they would be keeping the dataset, code, and model weights private. The world promptly lost its mind.

For reference, language models assign probabilities to sequences of words. Typically, they express this probability via the chain rule as the product of probabilities of each word, conditioned on that word’s antecedents ![]() Alternatively, one could train a language model backwards, predicting each previous word given its successors. After training a language model, one typically either 1) uses it to generate text by iteratively decoding from left to right, or 2) fine-tunes it to some downstream supervised learning task.

Alternatively, one could train a language model backwards, predicting each previous word given its successors. After training a language model, one typically either 1) uses it to generate text by iteratively decoding from left to right, or 2) fine-tunes it to some downstream supervised learning task.

Training large neural network language models and subsequently applying them to downstream tasks has become an all-consuming pursuit that describes a devouring share of the research in contemporary natural language processing.

At NAACL 2018, AllenNLP released ELMo, a system consisting of enormous forward and backward language models trained on the 1 billion word benchmark. They demonstrated that the resulting model’s representations could be used to achieve state-of-the-art performance on a number of downstream tasks.

Subsequently, Google researchers released BERT, a model that uses the Transformer architecture and a fill-in-the-blank learning objective that is ever-so-slightly different from the language modeling objective.

If you work in or adjacent to NLP, you have heard the words “ELMo” and “BERT” more times over the last year than you have heard your own name. In the NLP literature, they have become veritable stop-words owing to the popularity of these techniques.

In December, Google’s Magenta team, which investigates creative applications of deep learning, applied the Transformer-based language modeling architecture to a dataset of piano roll (MIDI), generating piano pieces instead of text. Despite my background as a musician, I tend not to get excited about sequence generation approaches to music synthesis, but I was taken aback by the long-term coherence of the pieces.

Fast-forward back to Thursday: OpenAI trained a big language model on a big new dataset called WebText, consisting of crawls from 45 million links. The researchers built an interesting dataset, applying now-standard tools and yielding an impressive model. Evaluated on a number of downstream zero-shot learning tasks, the model often outperformed previous approaches. Equally notably, as with the Music Transformer results, the generated samples appeared to exhibit more long-term coherence than previous results. The results are interesting but not surprising.

They represent a step forward, but one along the path that the entire community is already on.

Pandemonium

Then the entire world lost its mind. If you follow machine learning, then for a brief period of time, OpenAI’s slightly bigger, slightly more coherent language model may have overtaken Trump’s fictitious state of emergency as the biggest story on your newsfeed.

Hannah Jane Parkinson at the Guardian ran an article titled AI can write just like me. Brace for the robot apocalypse. Wired’s Tom Simonite ran an article titled The AI Text Generator That’s Too Dangerous to Make Public. In typical modern fashion where every outlet covers every story, paraphrasing the articles that broke the story, nearly all news media websites had some version of the story by yesterday.

Two questions jump out from this story. First: was OpenAI right to withhold their code and data? And second: why is this news?

Language Model Containment

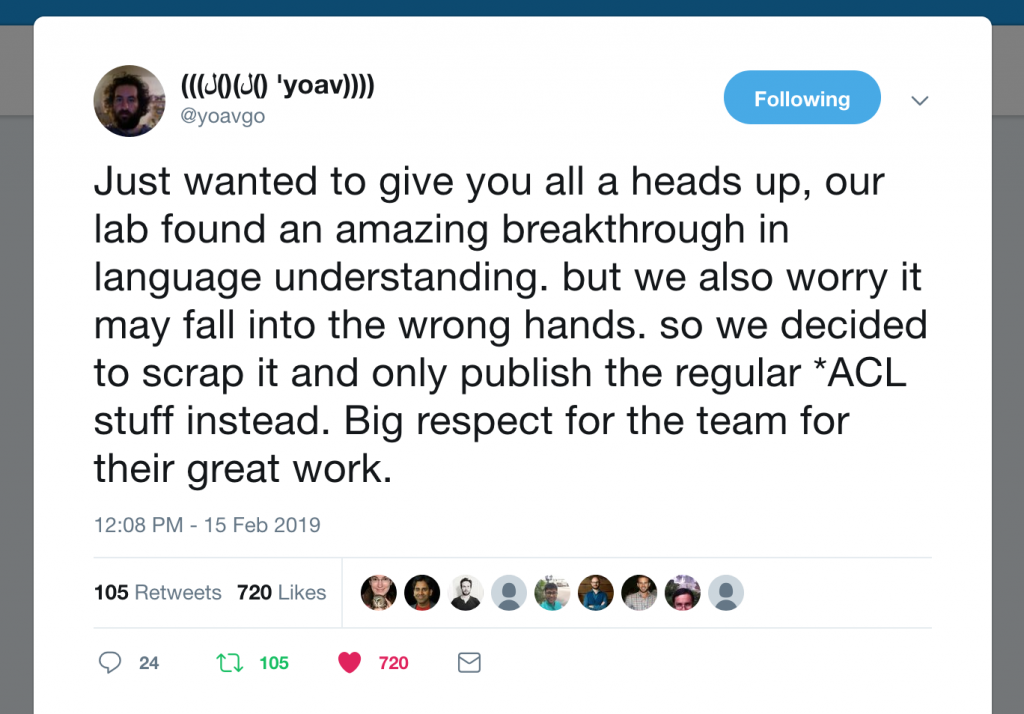

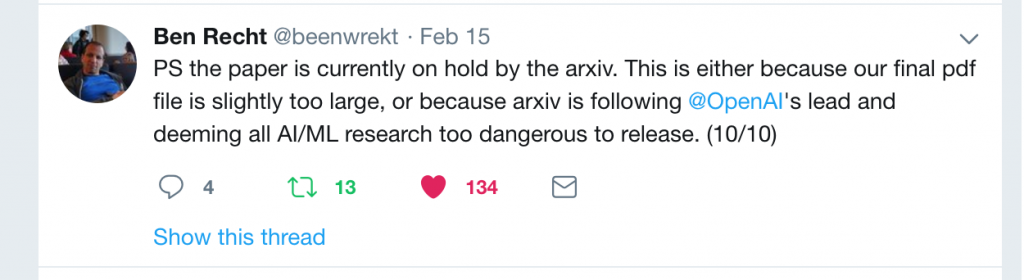

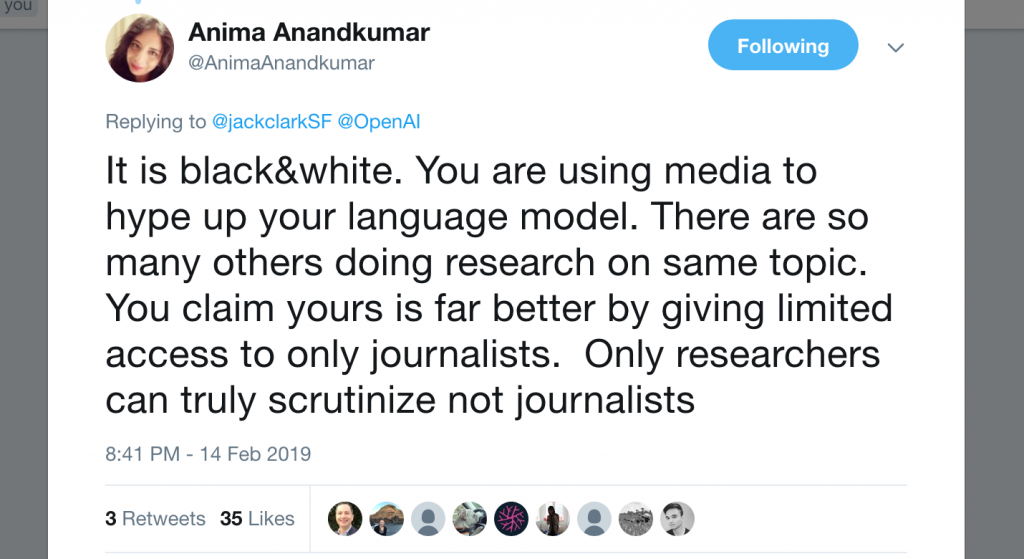

Over the past several days, a number of prominent researchers in the community have given OpenAI flack for their decision to keep the model private. Yoav Goldberg, Ben Recht, and others got in some comedic jabs, while Anima Anandkumar led a more earnest castigation, accusing the lab of using the “too dangerous to release” claims as clickbait to attract media attention.

In the Twitter exchange with Anandkumar, Jack Clark, their communications-manager-turned policy-director, donned his communications cap to come to OpenAI’s defense. He outlined several reasons why OpenAI decided not to release the data, model, and code. Namely, he argued that OpenAI is concerned that the technology might be used to impersonate people or to fabricate fake news.

I think it’s possible that both sides have an element of truth. On one hand, the folks at OpenAI speak often about their concerns about “AI” technology getting into the wrong hands, and it seems plausible that upon seeing the fake articles that this model generates that they might have been genuinely concerned. On the other hand, Anima’s point is supported by OpenAI’s history of using their blog and outsize attention to catapult immature work into the public view, and often playing up the human safety aspects of work that doesn’t yet have have intellectual legs to stand on.

Past examples include garnering New York Times coverage for the unsurprising finding that if you give a reinforcement learner the wrong objective function, it will learn a policy that you won’t be happy with.

After all, the big stories broke in lock step with the press release on OpenAI’s blog, and it’s likely that OpenAI deliberately orchestrated the media rollout.

I agree with the OpenAI researchers that the general existence of this technology for fabricating realistic text poses some societal risks. I’ve considered this risk to be a reality since 2015, when I trained RNNs to fabricate product reviews, finding that they could fabricate reviews of a specified product that imitated the distinctive style of a specific reviewers.

However, what makes OpenAI’s decision puzzling is that it seems to presume that OpenAI is somehow special—that their technology is somehow different than what everyone else in the entire NLP community is doing—otherwise, what is achieved by withholding it? However, from reading the paper, it appears that this work is straight down the middle of the mainstream NLP research. To be clear, it is good work and could likely be published, but it is precisely the sort of science-as-usual step forward that you would expect to see in a month or two, from any of tens of equally strong NLP labs.

THE DEMAND-DRIVEN NEWS CYCLE

We can now turn to the other question of why this was deemed by so many journalists to be newsworthy. This question applies broadly to recent stories about AI where advances, however quotidian, or even just vacuous claims on blogs, metastasize into viral stories covered throughout major media. This pattern appears especially common when developments are pitched through the PR blogs of famous corporate labs (DeepMind, OpenAI and Facebook’s PR blogs are frequent culprits in the puff news cycle).

While news should ideally be driven by supply (you can’t report a story if it didn’t happen, right?), demand-driven content creation has become normalized. No matter what happens today in AI, Bitcoin, or the lives of the Kardashians, a built-in audience will scour the internet for related new articles regardless. In today’s competitive climate, these eyeballs can’t go to waste. With journalists squeezed to output more stories, corporate PR blogs attached to famous labs provide a just-reliable-enough source of stories to keep the presses running. This grants the PR blog curators carte blanche to drive any public narrative they want.

I appreciate the media reflection here, except that bit at the end has me concerned. While there are those who are scouring for those things, I am given to understand that a common misconception about, say, people reading about the Kardashians, are mostly being fed this stuff. The demand is created once a certain person sees a headline or a link about a Kardashian, they are not typically setting up Google alerts and trawling through archives and web searches looking for new info; this latter type is rather more marginal in population than the type who is simply easily moved to pick up a tabloid, click a link, or even just not change the channel.

I would argue that a similar (though I dont want to overstate that similarity) principle applies to AI and bitcoin, both of which are segments where things can change fast, and many people who are interested in it dont want to be left, even if they aren’t actively researching it themselves.

I know I personally will click on a link about a cryptocurrency story but I am rarely actively searching it out.

Hi, My name is Gautam from India, I work as a Research Assistant in a Neuroscience Lab. Your blogs are interesting and gripping. The OpenAI blog was eye opener, thank you for that.

I have one question, Can you please give some tips on how I can write good articles and use a very elegant language style like you have done ? Its really awesome the way you write in research papers/blogs because it sort of gets to my head very quickly because there is so much clarity.

Hi Gautam, that’s very kind of you. I don’t know that I can pack all of my opinions about writing style into a single comment but sometimes I try to collect these thoughts and write them down. Last year I wrote this set of opinions on technical writing: https://approximatelycorrect.com/2018/01/29/heuristics-technical-scientific-writing-machine-learning-perspective/

There’s some other aspects about telling a story—choice of language, rhythm, etc, that I don’t touch there, but it’s something.

Ok thank you, ah I thought this would be a private comment 🙂

However, what makes OpenAI’s decision puzzling is that it seems to presume that OpenAI is somehow special—that their technology is somehow different than what everyone else in the entire NLP community is doing—otherwise, what is achieved by withholding it?

I thought that this was answered in OpenAI’s original blog post about the topic? They acknowledge that the result is likely to be soon replicated by someone else, but they are hoping to stimulate discussion and to buy a little time for figuring out how to deal with this kind of thing before someone releases their version. From the post:

This decision, as well as our discussion of it, is an experiment: while we are not sure that it is the right decision today, we believe that the AI community will eventually need to tackle the issue of publication norms in a thoughtful way in certain research areas. Other disciplines such as biotechnology and cybersecurity have long had active debates about responsible publication in cases with clear misuse potential, and we hope that our experiment will serve as a case study for more nuanced discussions of model and code release decisions in the AI community.

We are aware that some researchers have the technical capacity to reproduce and open source our results. We believe our release strategy limits the initial set of organizations who may choose to do this, and gives the AI community more time to have a discussion about the implications of such systems.

Hi Kaj,

Thanks for the thoughtful comment. In short, *attempting to address* and *convincingly answering* are not the same thing. We’re left with the issues that 1) the media blitz was unwarranted in the first place 2) that there is nothing achieved by their withholding of this particular model 3) that if you want to start a serious discussion about malicious uses of generative models, a PR stunt is the wrong vehicle.

We should have a serious public conversation about the risks associated with machine learning in the real world. You do that by seriously considering the underlying social problems and the actual threats posed by this technology. By slurrying together their PR with a shallow discussion of dangers, OpenAI has done little to advance a mature public discourse on these issues. I respect the researchers at OpenAI, and many have done excellent technical work, but they persistently mishandle the press and have to date exhibited immaturity vis-a-vis social problems.

Zach, thanks very much for this article, especially the links to related work.

I fell for the hype to a certain extent, and your article helped get me grounded in reality.

Might I offer another perspective on why this was newsworthy?

Most ordinary people simply cannot keep up with news in AI and NLP. What may seem like ho-hum, normal science to you still seems quite impressive, even stunning, to people who have passing understanding of AI and machine learning but not a deep familiarity with the rapidly evolving state-of-the-art.

I daresay even you may have lost some perspective about just how truly remarkable the performance of these systems is, and how much more realistic are their outputs compared to, say, 5 years ago.

I’ve been aware of machine learning since the 1980s, even published a couple papers back then in the area, but I moved into different areas of research and can now only barely keep up with the results, much less the technical details of the new algorithms and hardware. I knew about word2vec and similar technologies, but I had no idea that these systems could now produce long passages of connected text that were so coherent.

Anyway, thanks again.

I direct the Center for Communication and Health at Northwestern, and also have interest in NLP, dialogue systems, and healthcare. If you’d like to talk about these ideas sometime, let me know.

–bruce

Hi Bruce,

Thanks for the thoughtful comments! I think you are right that the public should be informed of the current state of the art and have been a proponent of such outreach throughout my PhD and young faculty life. It’s among the reasons why I run this blog. But, I don’t think splashy press release for a model muddled perplexingly with a poorly-articulated policy agenda is the right vehicle for getting this information out there.

Would love to meet up next time I’m out by Chicago/Northwestern and talk about ML/NLP for healthcare.

Cheers,

Zack

Please do drop me a line next time you’re in Chicago.

–bruce

If it’s written in Python, it’s machine learning; if it’s written in PowerPoint, it’s ‘AI’.

Whenever I see ‘AI’ I rewrite it in my head as ‘statistics’.